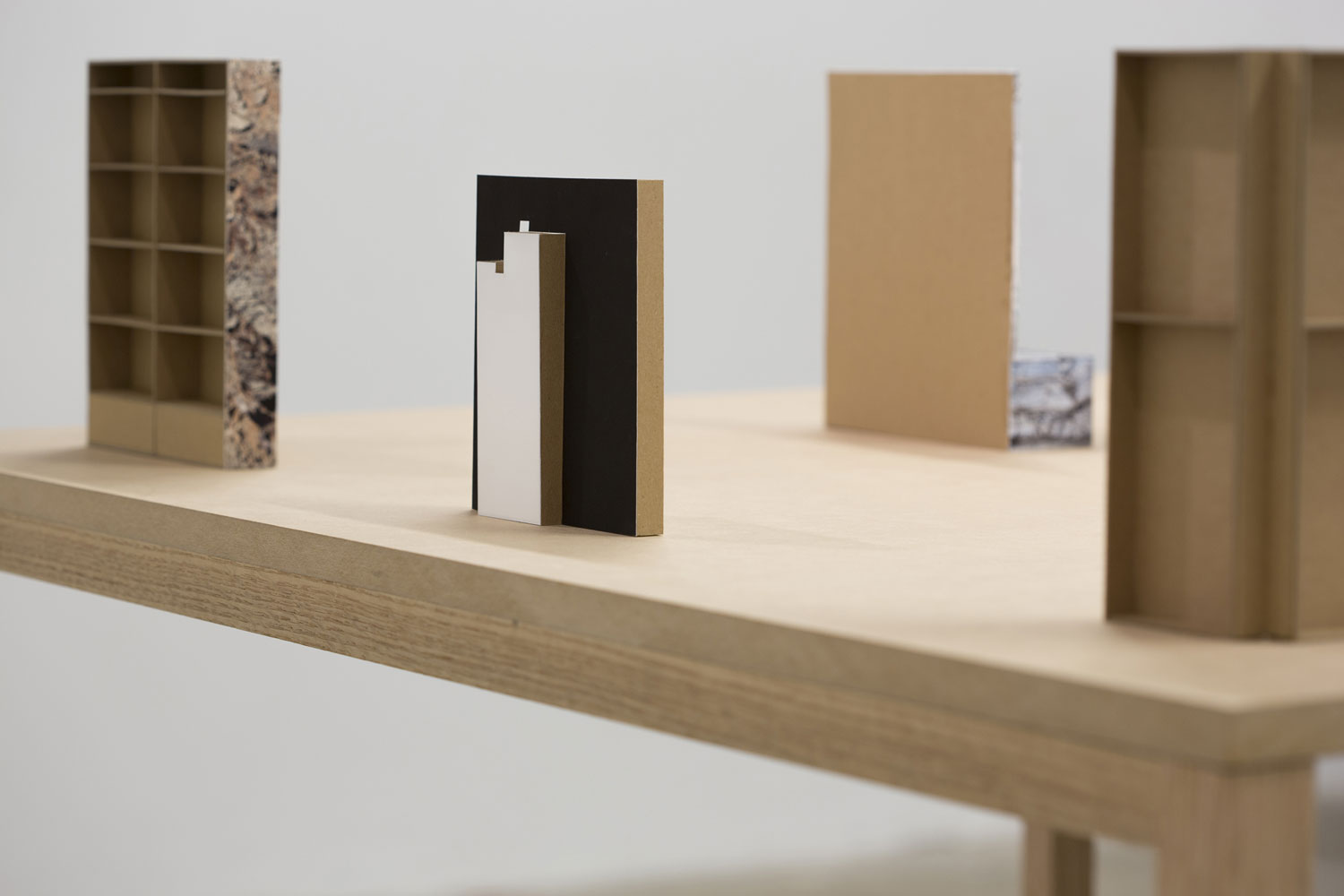

Room Plan, 2014

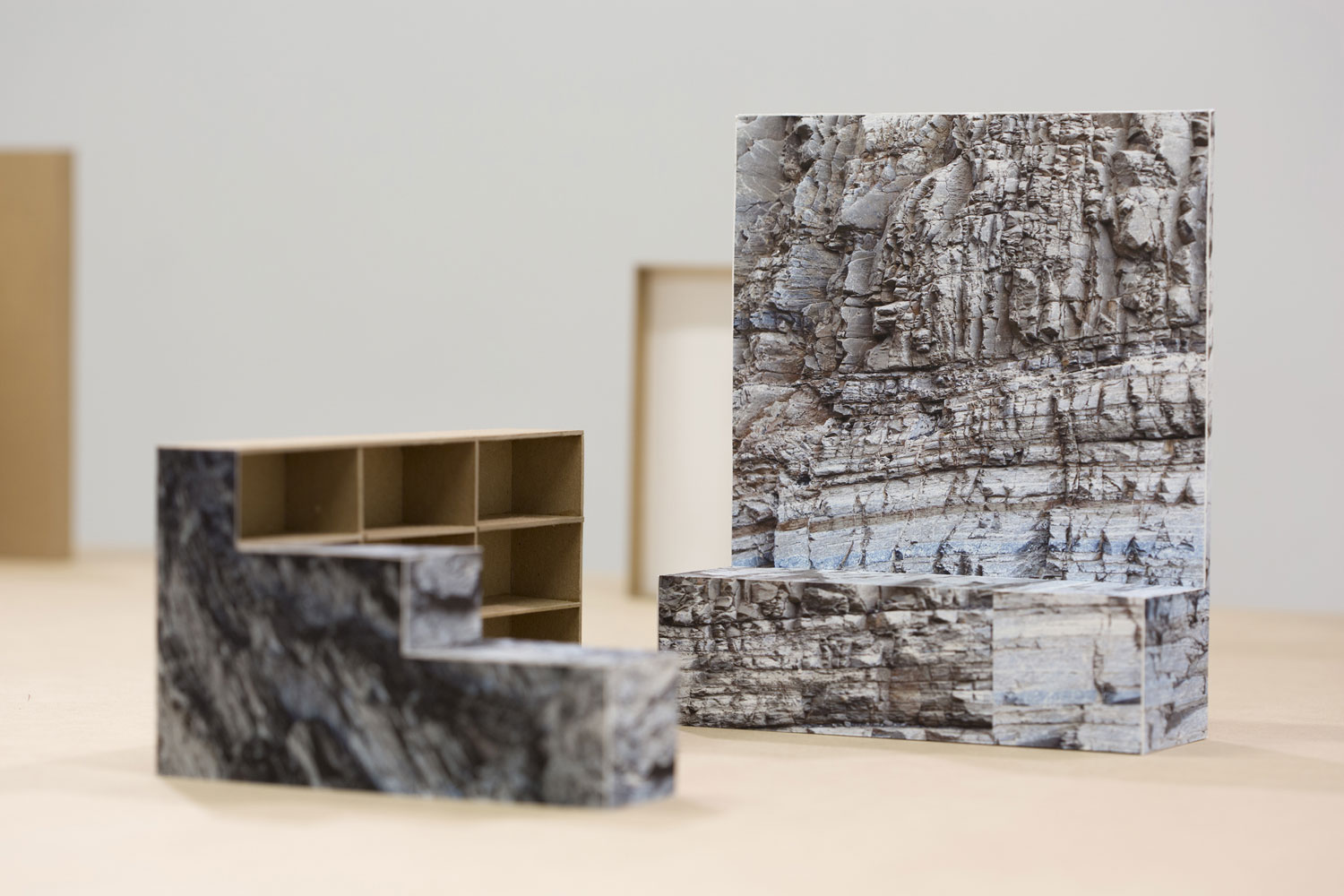

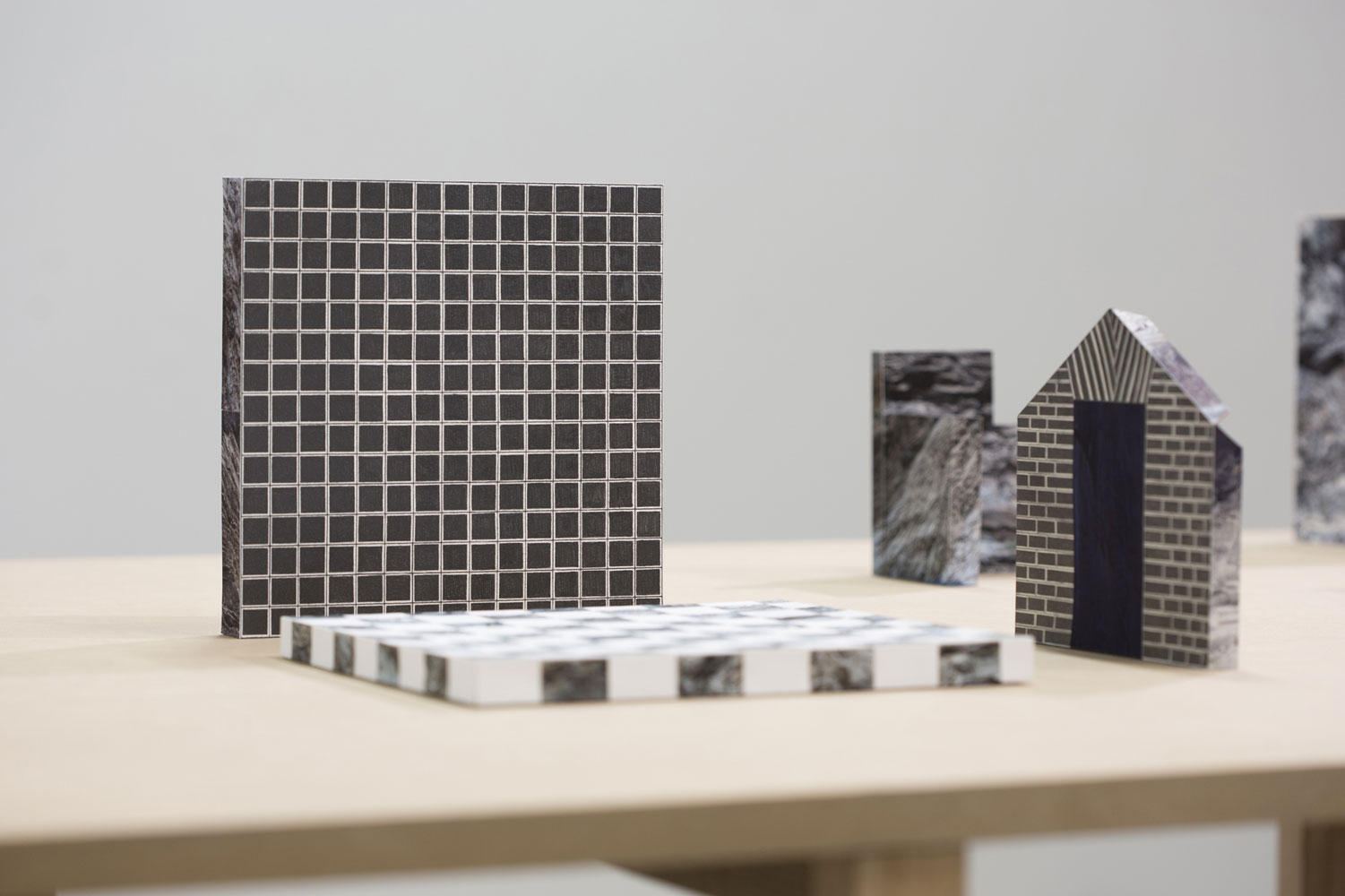

Installation view, series of 13 small-scale models on custom-made table, chipboard, inkjet archival prints, MDF, oak

4’ x 8’ x 30’’/122 x 244 x 76.2 cm

Room Plan

Joseph Gross

In 1787, Russian field marshal Grigori Aleksandrovich Potemkin created villages made of “canvas and pasteboard”[1] in anticipation of Catherine the II’s arrival.[2] Potemkin’s goal was to make the landscape much more attractive to the emperor, with whom he was said to be smitten, with hopes of impressing her.[3] In his 1898 essay, “Potemkin City,” Architect Adolf Loos critiques modern day Vienna by equating it to a Potemkin village. He laments Vienna’s inability to produce an architecture for its own time and states that Vienna appears as a “city of nothing but aristocrats,”[4] with its “Renaissance and Baroque palaces that are not actually made out of the material of which they seem.”[5] With the multipart installation Room Plan, artist Ofra Lapid creates a miniature Potemkin city, although her deception appears less designed to impress and much more so to comfort.

Room Plan consists of a group of fifteen miniature interiors modeled after both Lapid’s own lived in spaces and rooms created by architect Adolf Loos, whose work and writing influence her greatly. The work appears to be part of Lapid’s evolution as an artist, as prior to Room Plan, she created models but stopped short of displaying them in the round. In Broken Houses (2012), she constructed a series of miniature houses and barns with wood and inkjet prints, photographed them in their various levels of destruction, and displayed the results. The casual viewer might be fooled at first glance and mistake Lapid’s models for actual architecture, but the sterile negative space and the color pixilation on the facades should allow viewers to quickly realize the objects as replicas. Things are slightly more ambiguous with her inkjet print, Interior (after Loos) (2013), a framed photo of a cardboard recreation of one of the rooms in Adolf Loos’s Villa Muller (1930). The cardboard constructed interior, shadowed in dark tones, may be mistaken for an actual room, and acts as a bridge between Broken Houses and Room Plan. The models in Room Plan are not mediated through a camera lens, so there is no question about the reality of the objects, but photography exists in the form of inkjet prints that are affixed to a number of the structures. With the use of these prints, photographs of natural sites experienced during her time spent in California’s Death Valley, Lapid does not create a seamless transition from the outside to the inside similar to that of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Kaufmann House (Fallingwater) (1935), but instead offers a jarring recognition of our place on earth, our relationship to our lived in spaces, and the footprints that we leave.

Lapid has spoken extensively about her connection to Loos’s influence on Room Plan, and this does not come as a surprise knowing that Loos’s major architectural legacy is Raumplan, an “arrangement of related spaces into a harmonic indivisible whole and into a spatially-efficient composition.”[6] Lapid plays with this idea by providing viewers a carefully laid out series of interiors and offering them a phenomenological experience where they become aware of both the architectural and the natural worlds, as well as their pasts and presents. A print of a waterfall is affixed to the small door that stands closest to the table’s edge and acts as an orifice for a natural world seeking solace from the manmade. Once inside, things become calm and somewhat anesthetic. The furnishings, both those that are covered by Lapid’s photographs and those that remain bare, play the role of simulacra as explained in Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation. The viewers are drawn to these images of the natural world because they know that they are fake; this allows them to believe that the outside world is real and not the simulation that it has become.[7] By looking at photographs of natural landscapes, perhaps viewers will forget that much of the natural landscape has disappeared in favor of the growth of the capitalist system, and perhaps the visible construction, created with what Lapid refers to as cheap materials, allows viewers to believe in the quality of the architectural landscape by which they are surrounded despite its diminishing quality.

With Room Plan, Lapid has created a Potemkin village for a post-postmodern age. No longer are we concerned with appearing prosperous in a rapidly industrializing nation, but instead we are learning how to live in a technologically revolutionized world. The authentic no longer exists, but after viewing Room Plan perhaps viewers will be persuaded into feeling somewhat more at ease when stepping out into the not so real world.

[1] Adolf Loos, “Potemkin City,” in Spoken into the Void: Collected Essays 1897-1900 (Cambridge MA and London: The MIT Press, 1982),95.

[2] Ibid.,140

[3] Ibid., 140.

[4] Ibid., 95.

[5] Ibid., 95.

[6] Heinrich Kulka quoted in Leslie Van Duzer and Kent Kleinman, Villa Müller: The Work of Adolf Loos (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994), 38.

[7] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994), 12-13.